SJ Farmers Don`t Reap What They Sow

Ruggedly independent Garden State farmers could put the future of agriculture at risk

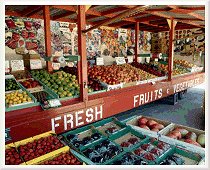

Ruggedly independent Garden State farmers could put the future of agriculture at risk Those farm stands groaning with summer fruits and vegetables may be colorful and fun places to shop, but they're a woeful way to do business. That's the warning from experts and growers fearful for the future of the state's $276 million produce industry in a world of corporate farms and nationwide supermarkets.

"I don't want to be a futurist, but there is a major challenge to the viability of agriculture in New Jersey," says Adesoji O. Adelaja, dean of Rutgers University's Cook College in New Brunswick and executive director of the New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station. "If farmers don't implement changes," he adds, "we will continue to be concerned. But if they get together and have a vision, they can succeed by the power of one."

Adelaja says the practice of selling fruits and vegetables primarily at roadside stands and local auctions limits the demand for Garden State produce, reduces prices, and shrinks the acreage of state farmland. Today, New Jersey productive cropland totals 830,000 acres, down from 880,000 acres a decade ago.

While the idea of farmers uniting is hardly new, it was urged again last month by a task force sponsored by the New Jersey Department of Agriculture, the New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station and the New Jersey Farm Bureau. The group's 36-page report calls on farmers to form alliances with large growers and target big customers such as supermarkets and restaurant chains.

"The old way of doing business is fast becoming the wrong way of doing business," the task force says. It recommends cooperative marketing by New Jersey farmers to enable growers to take advantage of economies of scale and do business with chains that increasingly rely on a few exclusive providers of fruits and vegetables. The report notes that many New Jersey growers lack the time and expertise to identify outlets for their produce. These include brokers, wholesalers and distributors, as well as grocery stores and restaurants.

"The industry has changed and it's harder for small farms to get their product into the marketing system," says task force member John VanSickle, director of the International Agricultural Trade and Policy Center in Gainesville, Florida. "They're going to have to develop relationships with the large suppliers who have long-term relationships with these buyers."

Without such links, New Jersey farmers are being shut out of even their home markets. By some estimates, up to 90% of the produce in New Jersey supermarkets and grocery stores is shipped from California. That's quite a slap at local growers, whose top crops include cranberries, blueberries, peaches, asparagus, bell peppers, spinach, lettuce, cucumbers, sweet corn, tomatoes, snap beans, cabbage, escarole/endive and eggplant. The New Jersey Tomato Council is one example of a successful marketing cooperative. With a small governing body and a board of directors, the Cedarville-based council comprises 15 growers who market, brand, package, and distribute tomatoes and fresh asparagus.

This team strategy creates some loss of independence for growers, but the report says it leads to more customers, more stability, and rising prices and profits for growers.

Currently, independent growers "often feel that they are forced to accept low prices because they have few alternative markets for their product," the report says.

But habits are hard to change. "Co-ops are a perfect vehicle, but we are talking about an ideal world here," says Jim Quarella of Bellview Farms in Landisville. "In reality, with all your personality conflicts, it's hard for people to come together."

Alex Tonetta, who grows produce at A. Tonetta & Sons in Vineland, estimates that while 25% to 30% of farmers are willing to team up, many fiercely independent growers will hold out. "Hopefully, this report will stimulate progress," Tonetta says. "Either this report or going nearly out of business will drive farmers to cooperate."

Many farmers like Tonetta rely on old-school auctions, the biggest being the Vineland Cooperative Produce Auction Association, where customers such as grocery stores and restaurants bid for produce. The association keeps a percentage of the sales price and charges a membership fee.

Florida's VanSickle calls auctions an outmoded method of selling produce that barely exists outside New Jersey. "Traditionally, such terminal markets had a much larger role in providing produce to the retail chains, but now they pretty much bypass the terminal markets," he says.

Critics of the New Jersey auctions say they are costly for growers and fail to do the marketing and branding that it takes to promote New Jersey produce. The task force calls on the auctions in Landisville and Vineland to merge, modernize and strengthen their promotions. It further recommends third-party inspections to ensure quality produce.

Adelaja of Cook College says New Jersey is unique in that its farms are located near residential neighborhoods, which forces them to cope with a high cost of business and operate under stringent regulations. But he adds that farmers benefit from proximity to the large and affluent populations between Philadelphia and New York City.

"We see New Jersey as a land of opportunity," says Adelaja, who notes that the Agriculture Experiment Station provides research and support for New Jersey farmers. "We want to help produce farmers work together. But we can't do it for them. We can only support them."

Content provided by NJBiz.

advertisement

Author: Scott Goldstein--NJBiz

Archives

Collingswood

A Southern Mansion

Light up the Night

Dining Alfresco

Sink or Swim

Throwing Shade

The Outdoors in Order

The Foundation

A New Spin on Swim

Gloucester Township

Wonderful Water

The Foundation: June, 2015

Community Connection: Moorestown

Things to Do

Cinnaminson

More...